Are Coliforms and Enterobacteriaceae the same thing?

Some interesting facts about Enteros and Coliforms

January 18, 2018

If you look up Coliforms and Enterobacteriaceae in Wikipedia and read the first two lines:

“Coliform bacteria are defined as rod-shaped Gram-negative non-spore forming and motile or non-motile bacteria which can ferment lactose with the production of acid and gas when incubated at 35–37°C. They are a commonly used indicator of sanitary quality of foods and water.”

“The Enterobacteriaceae are a large family of Gram-negative bacteria that includes, along with many harmless symbionts, many of the more familiar pathogens, such as Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Yersinia pestis, Klebsiella, and Shigella. Other disease-causing bacteria in this family include Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter.”

One might get the impression these are two completely different groups of bacteria. That may be how Wikipedia works, one person wrote one article and another wrote the other so the style is somewhat different. In any case, when testing food in a microbiology lab, there isn’t a whole lot of difference between the two.

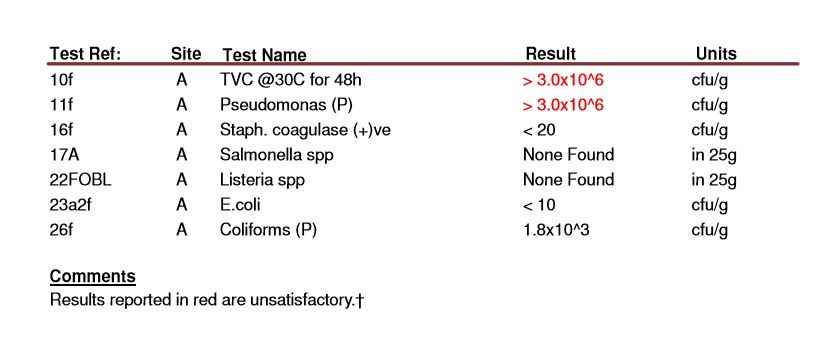

Both Coliforms and Enterobacteriaceae (Enteros) are used as indicator organisms in microbiology. Most of them do not cause illness but where they come from, the environments in which they grow well and the way they die is the same for most foodborne pathogens. Therefore it is a good indication that if these bacteria are high in a food the likelihood of more sinister bacteria being present increases and vice versa.

But can these bacteria groups really be used interchangeably?

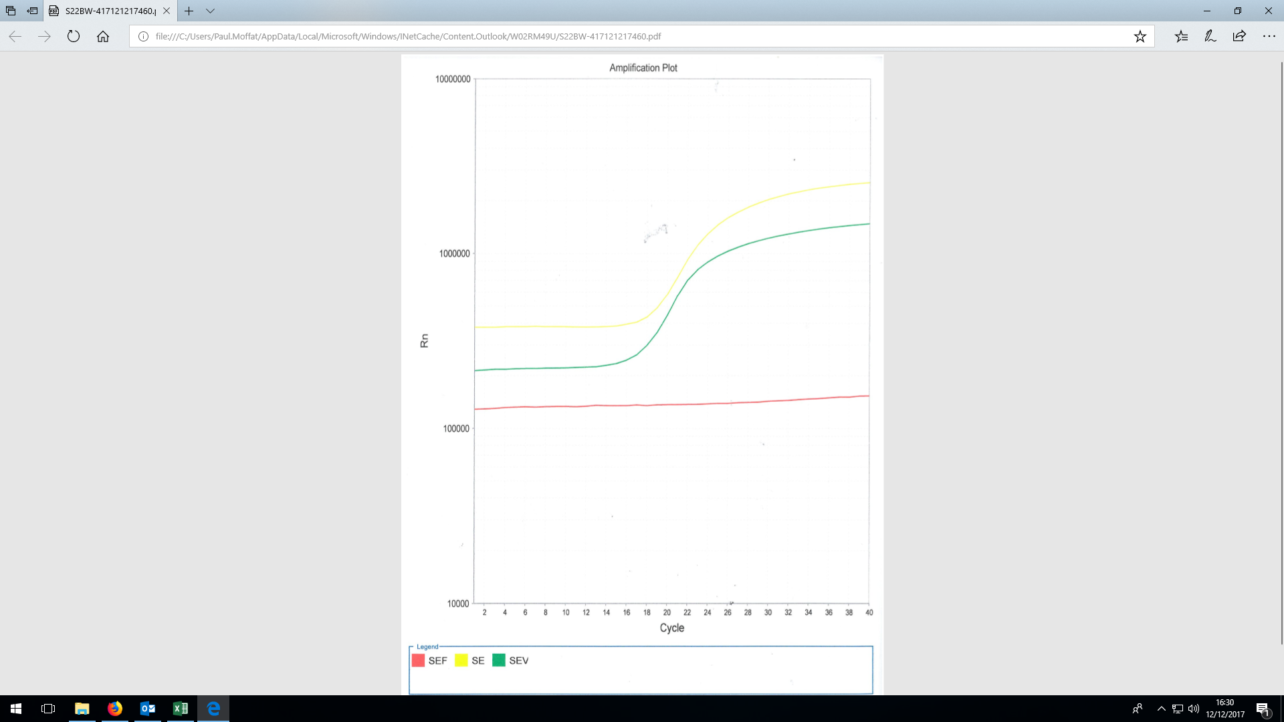

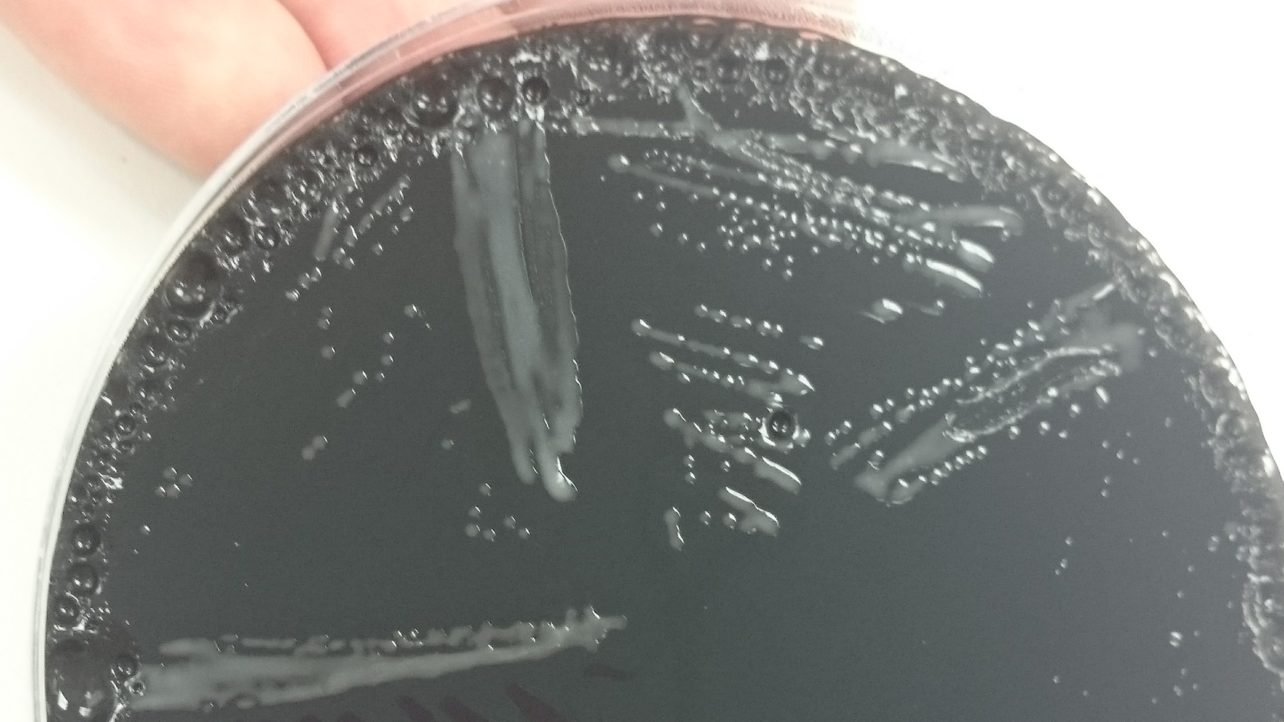

In the laboratory we use slightly different agars to grow Coliforms and Enteros, the difference being Coliforms metabolise lactose better than glucose so we use lactose as the main sugar when testing for Coliforms (Violet Red Bile Agar) and glucose for Enteros (Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar). The theory being not all Enteros can metabolize lactose but all Coliforms can metabolize glucose so the Coliform media is slightly more selective than the Entero media.

But how does this effect your test report? If you asked for both Coliforms and Enteros on the same sample, it would depend on the sample type if any real differences in the result would ensue.

For example, dairy products primary sugar is lactose so Coliforms grow better in these products and should probably be grown up on a lactose based agar. In meat where glucose is more prevalent but always at a low level overall, the number of Coliforms and Enteros would probably be very similar. In fact most other foods glucose or sucrose, which contains glucose, is much more common so the more general VRBGA should be used to capture as many indicator bacteria as possible.

Top Facts

- All coliforms are enteros but not all enteros are coliforms

- Coliforms prefer lactose as their sugar source but can metabolize glucose

- Not all enteros can grow on lactose alone but most can

- Both coliforms and enteros are good indicator organisms for sanitation in water and food, as they come from the same places, grow well under the same conditions and are killed in similar fashion as many pathogens

For Coliforms, Enteros and other microbiology testing available from Express Micro Science, please click on food testing.

More information on indicator organisms will be posted soon…