Controlling Botulinum

Controlling botulinum is a vital element of food safety that can have dire consequences if ignored.

February 24, 2022

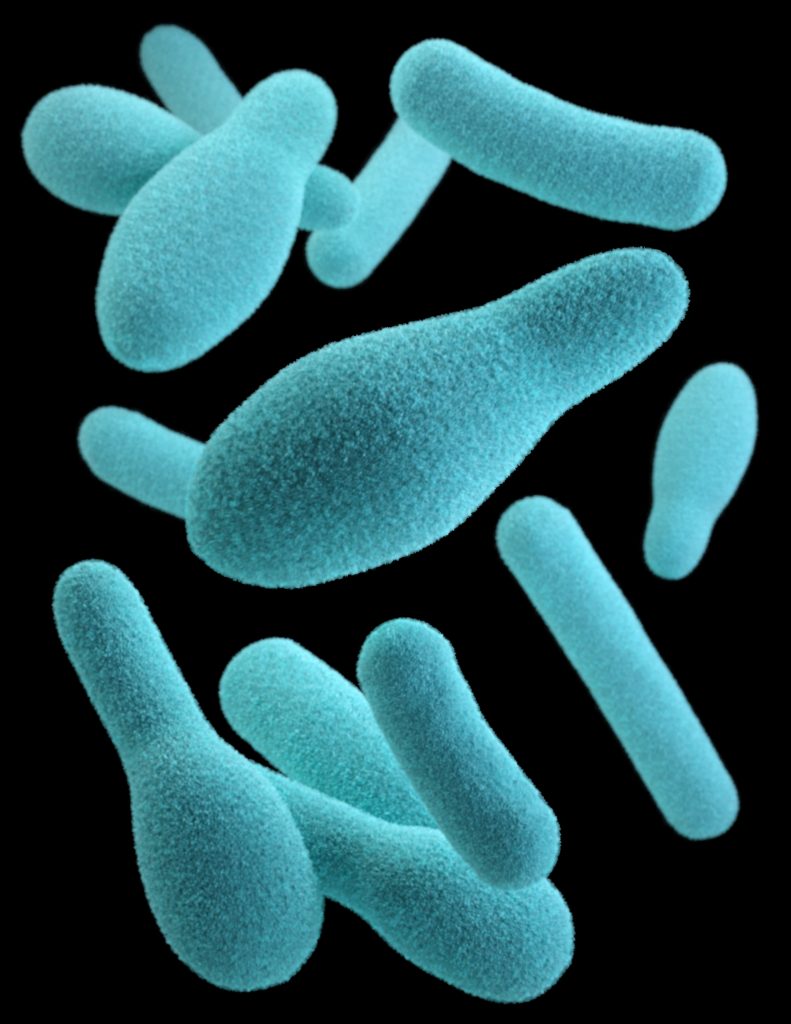

What is Botulinum?

Botulinum, or Clostridium Botulinum, is a species of the Clostridium. This bacterium can produce toxins in low-oxygen conditions that are deadly. Low oxygen foods include, vacuum packed, canned, and foods with high oil content.

Unlike many other pathogens, labs do not routinely test for C botulinum for two reasons;

It is so deadly that testing a representative sample of food does not provide enough assurance that the entire batch is free from the pathogen.

Most labs do not have the containment levels required to propagate such a deadly bacterium.

How it is controlled

So, if routine micro testing isn’t the answer what is?

There are a few ways you can control C botulinum:

- freezing the food, which works by inhibiting botulism rather than destroying it. This means that once the food is thawed, the botulinum can begin to take effect again, so short shelf-lives of < 10 days are required post thawing

- high heat / temperature combinations, e.g. like those used in canning

- having a short-shelf-life of < 10 days for product stored at temperatures > 3°C

- maintaining a low moisture content or pH throughout the food

Testing

At Express Micro Science we can test your product to prove that C botulinum cannot grow under chilled conditions, so that longer shelf-lives can be achieved.

- pH – food must be 5 or less throughout the food or throughout all components of complex foods

- Aqueous salt – food must have 3.5% or greater of salt in the aqueous phase throughout the food or components of complex food

- Water activity (aw) – food must have 0.97 aw or less throughout the food and throughout all components of complex foods

If your product meets any of the above requirements you are safe to extend your product’s shelf-life beyond 10 days.